TOXIC SUBLIME

403C.80 / 403C.6

2024

TOXIC SUBLIME

Work by Xiaoyang Wu (MSAUD '24) and Yuge Huang (MSAUD '24) for "Narrative Engineering, Myth & Machine", a MSAUD IDEAS Entertainment Studio taught by Natasha Sandmeier and Liam Denhamer. This studio investigates the dynamic relationship between technology, environment, and the human experience, revealing how tools both shape and are shaped by the worlds they inhabit. By exploring the narratives embedded in these interactions, this studio seeks to uncover the transformative power of innovation within interconnected systems.

Project Statement:

Crystals are often seen as beautiful and harmless objects. Their allure can be captivating, drawing people in with their natural beauty and supposed mystical properties. For centuries, people have been fascinated by crystals, using them for decoration, jewelry, and even healing practices. However, this perception of harmlessness can be deceptive, especially when it comes to the process of obtaining these gems.

Mining activities, particularly for gemstones, can have devastating impacts on the environment. The environmental impacts of gemstone mining can be severe, affecting land, water, and ecosystems. The process often involves deforestation, soil erosion, and contamination of water sources. These activities not only destroy habitats but also pose significant health risks to local communities.

The consequences of mining are far-reaching. Deforestation leads to loss of biodiversity, water pollution affects both wildlife and human populations, and soil erosion can render large areas of land unusable for agriculture. These environmental impacts highlight the destructive nature of mining activities.

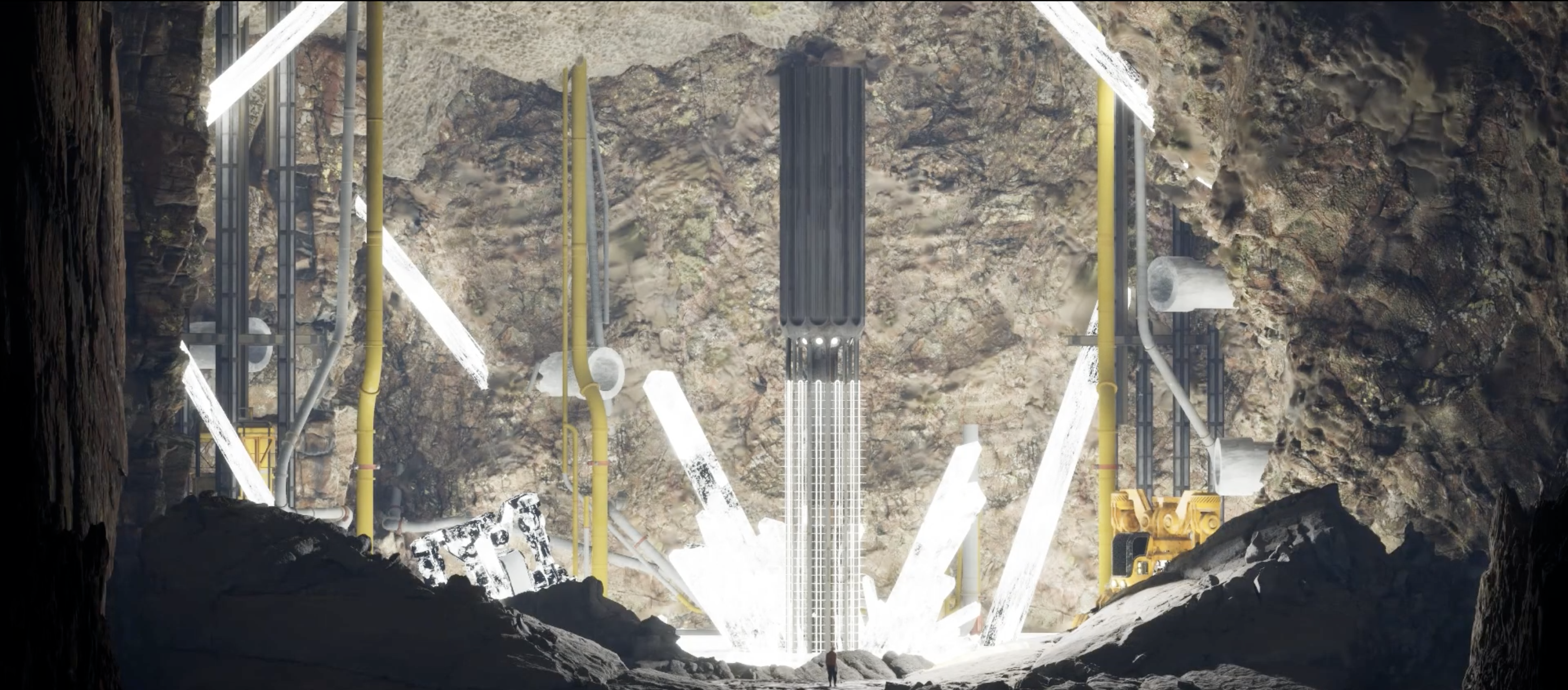

Toxic elements are released during the mining process, contaminating water sources and affecting wildlife and human health. In the Congo, cobalt mining has serious environmental and human impacts. In addition, mining of rare elements around the world leaves behind radioactive and toxic waste. Gold Mining Is Poisoning Amazon Forests with Mercury. The burning of gold-mercury releases large amounts of mercury into the atmosphere. To separate the gold, miners mix liquid mercury into the sediment. Gold mining leads to deforestation, which turns forests into contaminated ponds and drives large amounts of river bottom sediments.

This brings us to the concept of the 'toxic sublime' – the paradoxical beauty found in toxic environments. This idea shows how we find a strange allure in what is inherently dangerous.Real-world examples of the toxic sublime can be found in many industrial sites.

These locations, while often hazardous, possess a certain aesthetic appeal that draws photographers, artists, and curious onlookers.

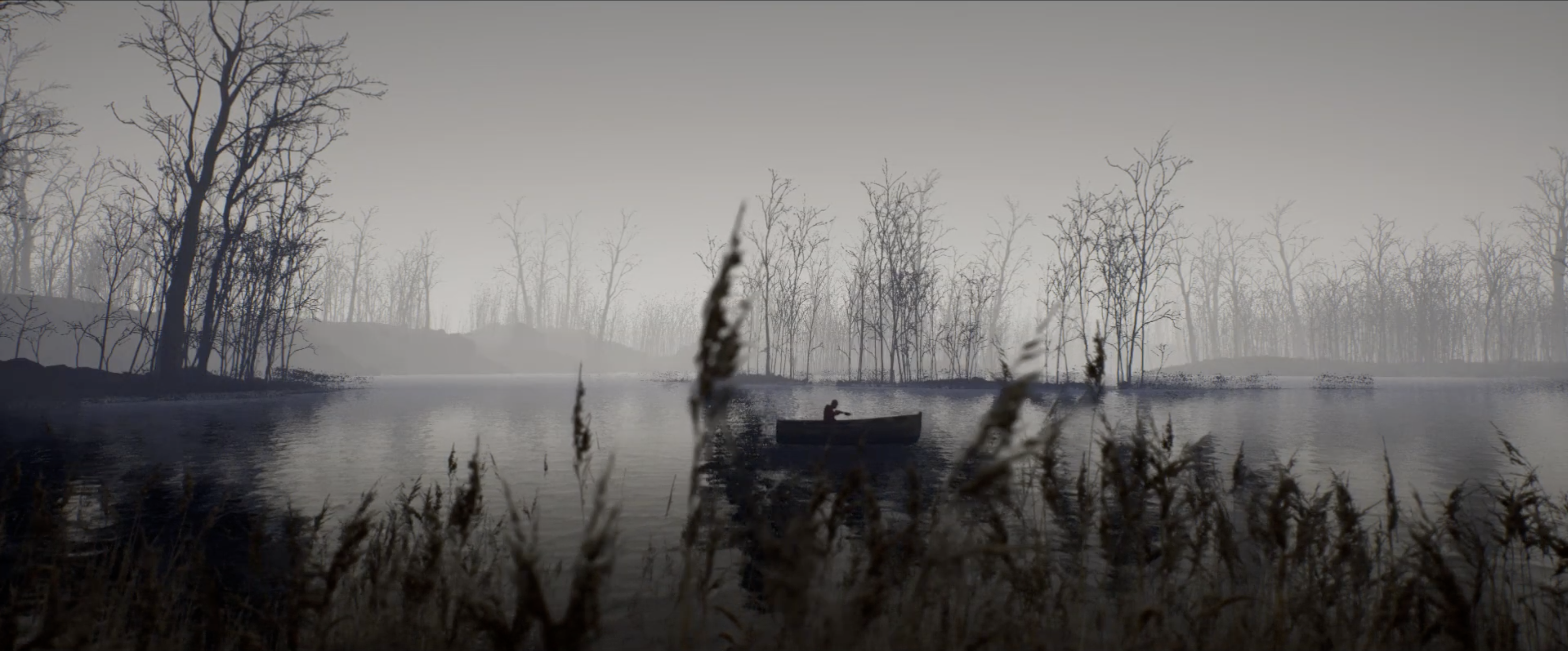

Despite knowing these risks, humans remain fascinated by danger. Shown in the picture are the lakes around the Siberian city known as Siberian Maldives.

The lake is blue, however, due to a chemical reaction between toxic waste elements from a local power station. Despite knowing that this lake is toxic, many people come to the lake to wander around and take pictures. People are attracted to these dangerous environments, whether out of curiosity, greed or other motives.

Around the world, people are often excited about things they know are dangerous for a variety of reasons. And there are always reasons to explain this desire for toxic sublime.

Our story is about an artisan miner goes on his journey to a corporation mine, harvesting crystals for himself while ignoring the danger in this toxic sublime.

itation on resilience, interconnectedness, and the delicate balance required to sustain both life and the planet.”

Narrative Engineering, Myth & Machine

The Landscape of Technological Narratives

*From the crude shovel reshaping our landscapes to the intricacies of the printing press revolutionizing knowledge dissemination, technological innovations have always stood at the forefront of human evolution. Yet, the narratives of these tools are not just tales of isolated brilliance; they are deeply woven into the fabric of their environments and the lives of their protagonists. These tools are the tangible embodiments of our innate desire to innovate, but they also bear witness to our journey as we live and grow with tools we’ve created, often making mistakes as we learn how best to use them.

This year we will research and work within the relationship between technology, environment, and protagonist. The environment shapes the challenges we face, the protagonist crafts the tool in response, and the tool, once deployed, reshapes that very environment, thereby influencing the needs and desires of the protagonist anew. It's a cycle of perpetual innovation and adaptation. A farmer in rural China or Italy (the story is the same across the world) is a protagonist of his own small world. One day, he wielded a simple shovel to carve a small irrigation channel from a stream into his fields. Over decades, this act didn't just transform his immediate landscape, but also led neighboring farmers to do the same. As more joined in, this collective effort transformed the entire region, turning what was a barren land into a flourishing agricultural hub. A shovel triggered an environmental and socioeconomic metamorphosis.

One of the most important technologies of all time is widely acknowledged as the printing press. Once a very labor and time-intensive process, the production of books escalated exponentially. In a world that relied up until that point on the relaying of information through word of mouth, widespread access to knowledge radically transformed the cultural landscape, eventually laying the groundwork for the Renaissance.

Keep in mind the intrinsic interdependency: for every tool there is an environment it alters and a protagonist it supports. This studio is not just about creating transformative tools, but about understanding and crafting the interconnected stories they tell within the ecosystems they inhabit and the lives they shape.

Remember also, that even small tools can lead to unimaginable change.*

Related Faculty |

Natasha Sandmeier, Liam Denhamer |