Ahead of Distinguished Alumni Lecture, Frederick Fisher (MArch '75) outlines a warm, rangy vision

May 7, 2025

The Founding Partner of Frederick Fisher and Partners, Frederick Fisher (MArch ‘75) is a self-described “liberal arts guy.” He is an avid reader, traveler, and arts-lover, and his approach to architecture reflects his innate intellectual curiosity and broad cultural and social perspective.

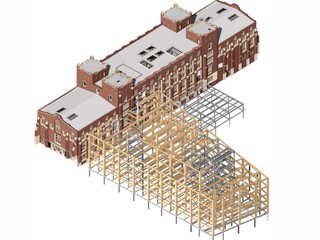

Fisher’s list of both projects and honors is towering. Among the former are the renovation of Princeton’s Firestone Library; MoMA/PS1 in New York; The Annenberg Community Beach House; Sunnylands Visitor Center and Gardens; Erburu and Fielding Galleries of the Huntington Library, Art Museum and Botanical Gardens; Santa Monica City Hall East; and the Jimmy lovine and Andre Young Hall at USC.

Fisher returns to Perloff Hall on Monday, May 12 to present this year’s Distinguished Alumni Lecture. Travis Dagenais, Director of Communications and Outreach at UCLA AUD, caught up with Fisher ahead of the event, tracing some of his favorite moments and insights from his early days in Los Angeles and unpacking a few projects along the way.

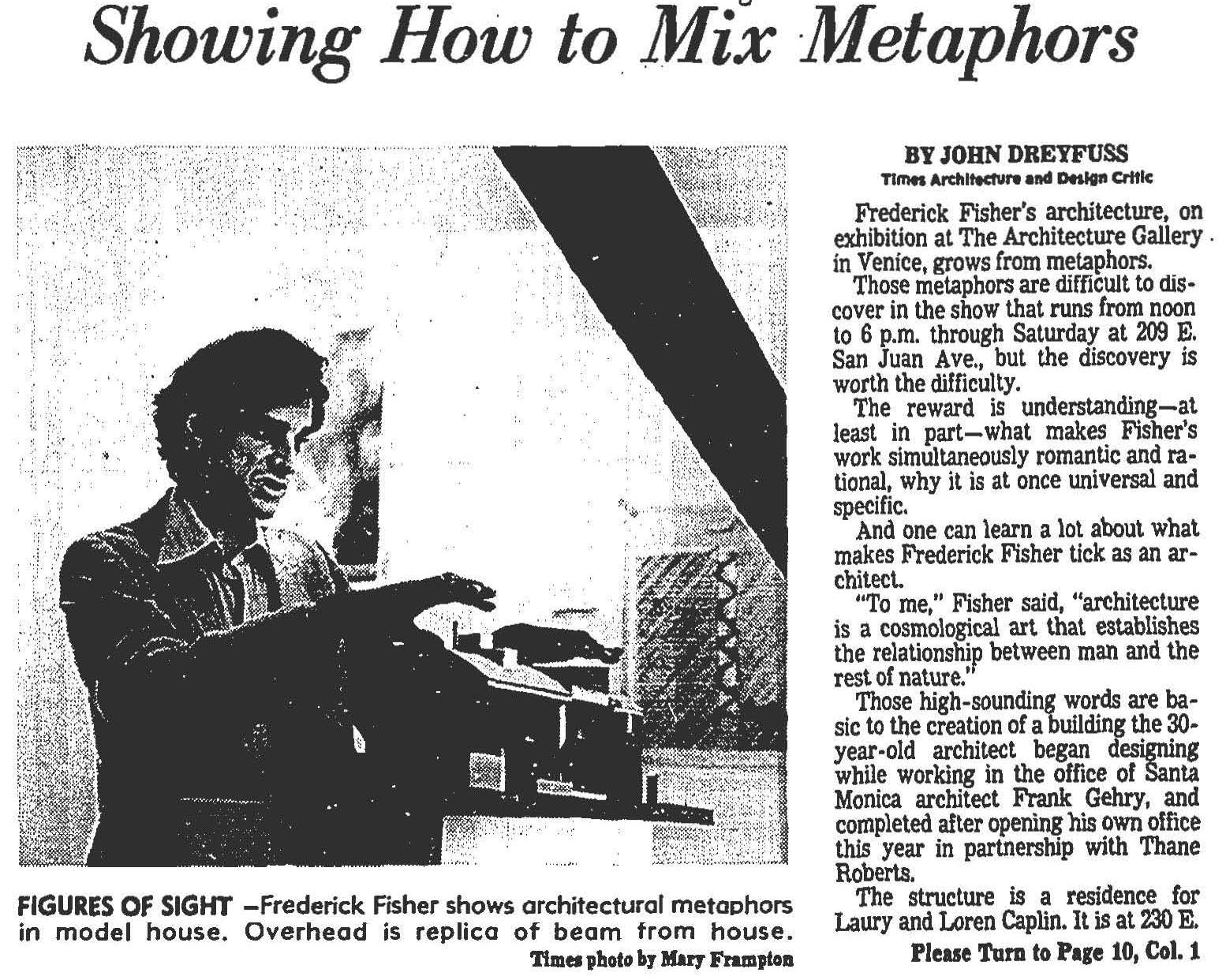

Fisher didn’t intend to study at UCLA (“I had never been to LA. And actually, I had zero interest in LA”), nor did he intend to stay here (“I always expected that I would be out of here the minute I graduated”) – but an immersion in the Los Angeles art world, and a serendipitous first job at Frank Gehry’s office, offered an irresistible pull for the curious, budding architect. The rest is history–or, as Fisher might say, once he found the right metaphors, “the building designed itself”.

“By whatever reason,” Fisher says, “I ended up at the right school, at the right moment in LA’s history, literally in the right neighborhood–and I was just like, ‘I can’t believe my luck.’”

AUD: Welcome back to Perloff Hall. I understand this was one of your very first entry points to Los Angeles.

FF: I had never been to LA before enrolling at UCLA. And actually, I had zero interest in LA. I didn't like it when I got here. I drove here from Cincinnati. When you came into Los Angeles from the east back in the early 1970s, it was not a pretty sight. It was a hundred miles of pollution-choked industry, suburban oblivion. My wife and I were nearly crying as if we just made the biggest mistake of our lives. The only reason I was going [to UCLA] was because I got rejected at every single graduate school I applied to. Berkeley included a note saying: “We are not going to be able to accept you, but UCLA has a new program, and if you would like, we will send your material down to them.” I didn’t even know [UCLA AUD] existed.

But, you know, things change quickly. We were living in Brentwood, I rode a bike to UCLA, got asthma in the process because the pollution was so bad. Unlike most of the other students, I was married – so I would work ‘til six, and then I got on my bike and went home and had dinner with my wife. But, architecture school is all-consuming. Everybody was working late and ordering pizza and getting crazy at night. In some ways, I feel that I missed out on that.

But it was just right for me because I came from Oberlin College studies in liberal arts–and UCLA had one of the few programs where, with a non-architectural bachelor’s degree, you could get a Master of Architecture in three years. And so there were mathematicians and English majors and scientists and all kinds of people that you wouldn't normally see in a professional architecture program. The faculty was also quite diverse intellectually and creatively. You could curate your own education; there was quite a variety. It was a perfect fit for me.

I didn't own a car, so I didn't explore the city. When I graduated, I got my first car–a used Datsun station wagon–and all of a sudden it was like: Amazing! There's this huge, interesting city out there.

Having the breadth of LA suddenly available–what did that do for you, as a curious person?

FF: Well, it's great for a curious person, because you realize that [LA] is a city of cities and there are many types of environments, and many types of people in many different neighborhoods.

By that time, I had gotten fairly immersed in the art world, and that is its own layer over the whole city. There's the Venice scene and the Pasadena scene, the museum scene and the gallery scenes. And so that placed me in an almost meta city, superimposed over the geographic and social and architectural city.

In my third year at UCLA, I saw Frank Gehry talk at the famous Whites and Grays Conference, and I thought: That's it. This guy, he knows art, he works with artists–he's not doing anything like anybody else. This is when he was doing the Donna O'Neil Hay Barn and the Ron Davis studio, and chain link and plywood and corrugated metal. I thought, This is the only guy I want to work for.

I had met [Gehry] a couple of times, and after I graduated from AUD, I called him up on the phone – “I am so interested in what you're doing, and I would just love to work in your office.” He said that's not possible, we don't have any positions available. So that was that. And literally the next day he called back and said, “Somebody just quit. I need somebody immediately. Can you come in?”

I feel like I've been blessed with some very lucky moments in my life, and that was one of them. But I also believe in the adage that you make your own luck. You have to put yourself in a position for things to happen.

Did you have a sense of what you were stepping into, the magnitude of it?

FF: I had no idea what to expect, but it was everything and more that I had hoped for. When I started [at Gehry], there were six people in the office–1977 or ‘78, a recession. It was this giant loft space on Cloverfield, and it was full of sculpture–a museum of contemporary art superimposed on an architecture office. A lot of empty desks and then, you know, Tony Berlant, Robert Irwin, Alexis Smith, John McCracken–all this stuff was just there. He was, at that moment, becoming the Frank Gehry that we all know and love. I’ve always admired the fact that, even at the worst time, economically, he took the biggest risks. He basically said, “I'm going to do this stuff no matter what.” And it wasn't all well-received; there were architects who just hated what he was doing. They said, “You know, you're destroying the profession, this crappy material, these cheap, cartoonish buildings you are doing.” He just took a lot of flak.

My entry into the office was as a model maker. He put me on Mid-Atlantic Toyota as a project architect, probably way too early. I'd go to his desk and he would scribble these crazy little drawings and say, “Go make a model of that.” It was basically just getting thrown off the boat into the water and then: sink or swim. I had no idea what I was doing.

Very different from your studio experience at AUD.

FF: Oh, yeah, it was. It was intense. But it was right in my core interests, which was art, and thinking about architecture in a different way. It was just so different than anything else that was going on.

Personally, what was inspiring you to keep studying and working with architecture?

FF: There were two lightning bolts. One was seeing Frank Gehry talk about his work. The other was reading [Robert Venturi’s] Complexity and Contradiction. He looked at everything from baroque architecture to late modern Italian postwar architecture to Jasper John’s “Flag” and Frank Stella–and just, that mixture. I thought, “Yeah, I want to give that a try.” I realized architecture can be so much more interesting than I thought it could.

Oberlin is a place where you can do things intellectually, academically, that you can't do anywhere else. Were you seeking more of that in graduate school?

FF: I wanted a mixture. I wanted to be able to explore my own direction, curate my own education. I wanted to bounce off different kinds of thinking and people. And that's exactly what I got. I got freedom; I got great, smart people that had angrily differing opinions; I got a great cohort of students; and I got Los Angeles, which I was learning was a pretty interesting place.

Did you intend to shack up here in California?

FF: No. I always expected that I would be out of here the minute I graduated. Then I got a job, and then I got my first house.

Los Angeles is a young city. It's a big city. It's a place where you come to be–you can come here and make your own way. When I got here, there wasn't really an establishment. Maybe there was one downtown, but not at UCLA. Over on the West Side, you had a sense of: It's okay, do your own thing. You don't have to worry or have permission. I valued my independence and being left alone with just: “Try it.”

Was there something special about that time in LA?

FF: Well, the excitement was around actually getting to build stuff. I was building my first house when I was just out of school. I was just starting out and didn’t really know that many people here.

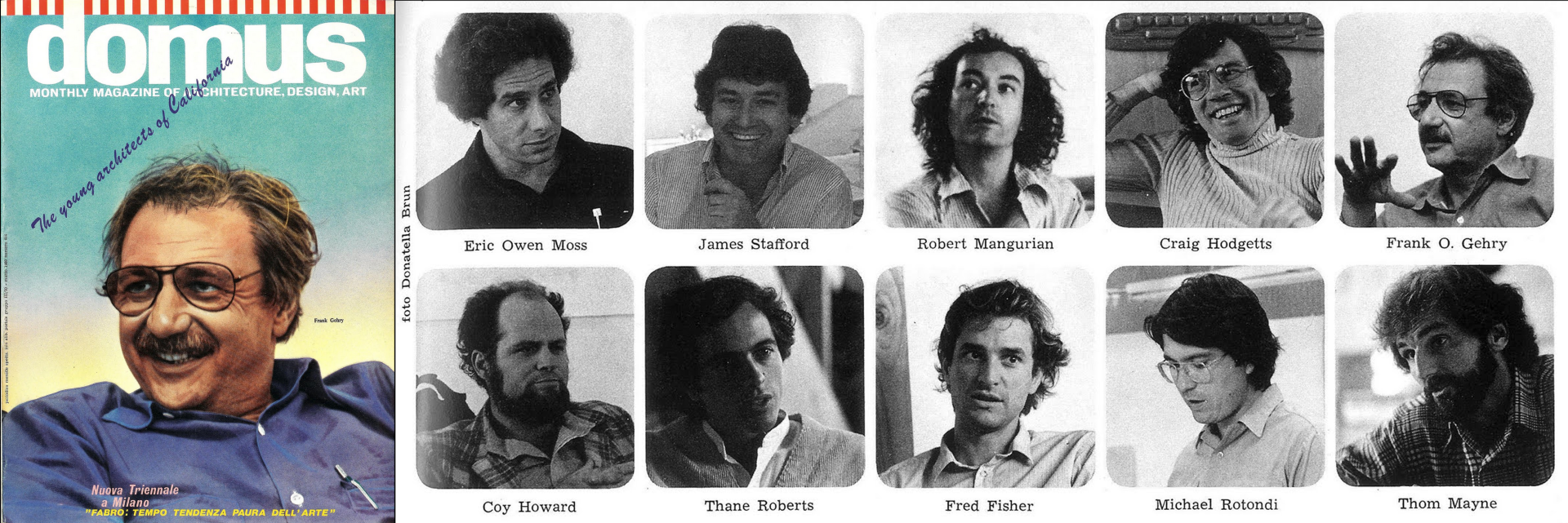

At that time there were all these journalists sniffing around wondering, “What's going on here?” You know, Wayne Fuji from Japan, Tim Street-Porter. And there was that famous issue of Domus magazine right about that time, Frank Gehry’s face on the cover [Domus 604, March 1980]. And inside were those buildings by those people in [that Venice Beach photo], and the house I was working on, my Caplin House, was included. It wasn't even finished yet–I hadn't even finished my first building, and now suddenly I'm in Domus.

Editor's Note: Domus 604, published March 1980, included the feature article "Ten California Architects" by Olivier Boissiere, who wrote: "The young architects introduced here, Frank Gehry, Fred Fisher/Thane Roberts, Craig Hodgetts/Robert Mangurian, Thom Mayne/Michael Rotondi, Eric Owen Moss/James Stafford, and Coy Howard are in their early thirties. They already have significant works to their credit; they are brilliant, often sparkling, and versatile."

When you look back now, do you think there's afterlives of that spirit that have affected you longitudinally?

FF: Being in Venice at that moment, art was all around. Going back to my childhood, I grew up going to art classes on Saturday morning, going to the Cleveland Art Museum. That just became a normal part of the way you think about the world. And then I studied art at Oberlin, and my eyes were opened to contemporary art. Then came AUD and Los Angeles, and living in Venice, hanging out with Frank Gehry and artists who were interested in architecture, like Ron Davis and Irwin and Turrell. I was going to art openings and collaborating with artists, art studios, art galleries, and living with art. Those were powerful experiences for me.

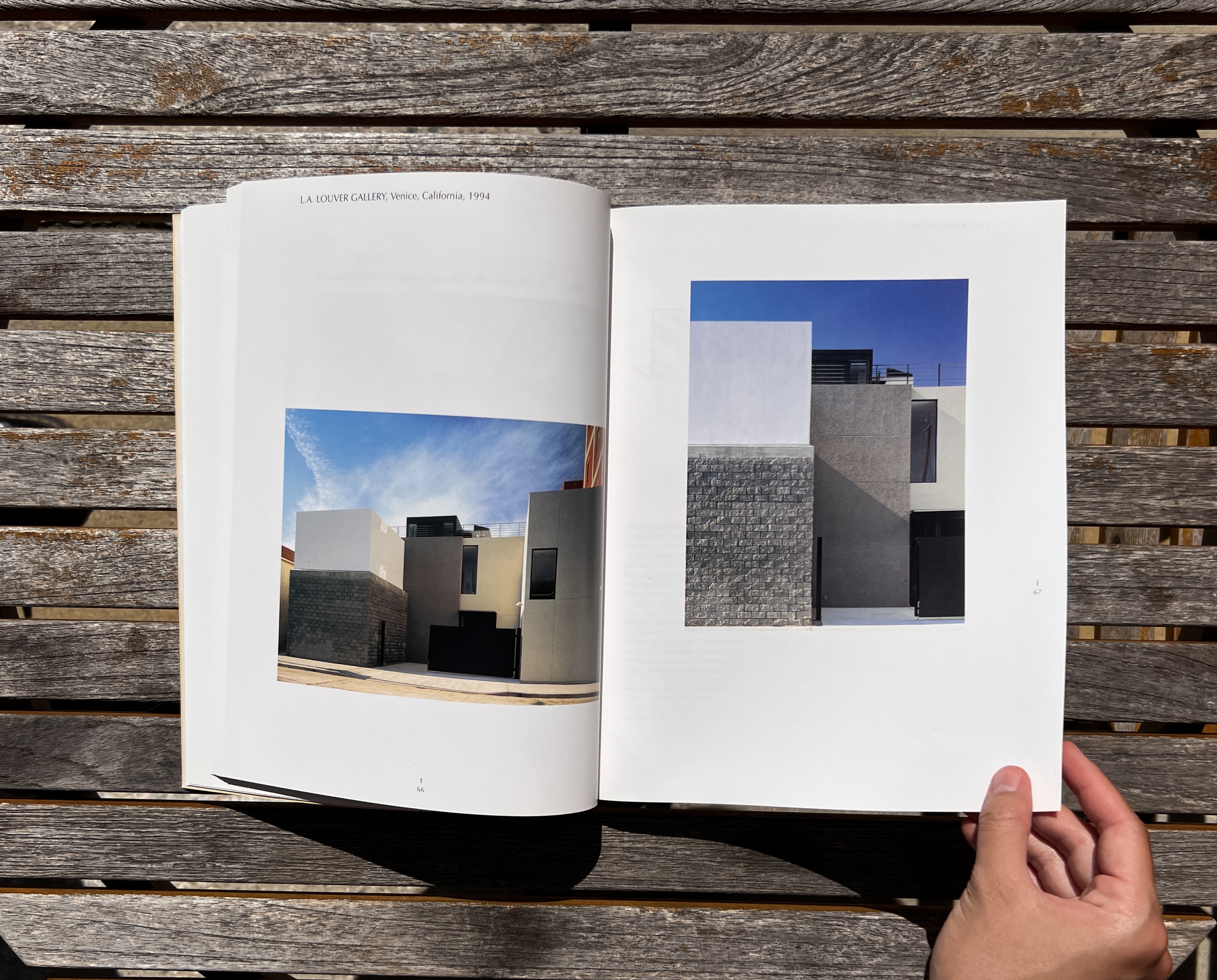

I got a big break from Peter Goulds doing the LA Louver Gallery. Got another big break from Eli Broad to do the Broad Foundation. Eli decided I needed to know what was going on in the museum world, so he sent me to Europe and I saw probably 40 museums in ten days: the early Saatchi collection and Schaffhausen and the cutting edge of the unselfconscious loft spaces. That was hugely influential. Robert Irwin's “light touch” about how art is not an object, it's an experience.

Drawing these connections between art and architecture–you’re a self-described “liberal arts guy,” and it seems like that education was profound for you.

FF: I think we understand each other, me and the liberal arts. I want to think about things in a narrative-, mission-driven way. I don’t start with, “I want to do a building that's shaped like this.” I start out with: What is the most senior idea? From there, it’s a hierarchy of mission, goals, strategies: What's the top idea, the simplest idea? And then, what are the three or four implications of that? And then, the six or eight strategies for achieving that?

The Colby College Museum of Art–I was brought into that by a friend in the art world, which is this incredible network, and these things weave together really efficiently. There was a selection process, and they put my name in the hat. During the site visit, the president of Colby College literally told me: there's no way we're going to hire an architect from Los Angeles.

In the president’s office, I noticed that there was a painting of a Shaker house; I took a picture of it. In Maine, they love their Shakers, they love their federal-style architecture. The campus of Colby College looks historic, all in that federal style, but much of it actually was built in the 1960s. I showed him a picture of that painting, and I said: I think the museum should seem as if it's the first building built on campus, not the most recent. It should be that elemental, almost like a Monopoly house.

Colby's art collection was at the time most strongly in early American art; that art was shown in houses, not in lofts or in museums. It was a domestic accoutrement. And so I talked about that, and I got the job.

What were some of the things that you thought about and that you talked about in order to make the project feel different for them?

FF: Number one was asking the question: What is the proper setting for the art that you have, and what is its story? And that story was about early America and that architecture–that elemental, federal-style architecture, a picture hanging on the wall in a smallish room with maybe red-colored walls, a building that is self-sufficient and it's sitting in the landscape and you could imagine that building being there by itself when there was nothing else there. And your campus came from that little house. And so, it had to do with: How do you understand your art and how do you understand yourself? What's your identity?

And so that was the story. We did it in a way that, as I say, the building designed itself.

Did the story change as you designed the project?

FF: It did. We did that building and they were very happy with it. And then there was another building they wanted to do–a studio building, different function but part of the same complex. And I said, Oh, that's easy. We're just going to do another Shaker house–we're going to build the Shaker Village that was here before you built your campus.

So we did that, and they came back for a third building and I thought, “We're just going to keep adding little Shaker houses.” But the project had an attitude by that point–we had added to it twice and it had reached the breaking point where you couldn't add to it that way again, efficiently. Also, they were collecting more contemporary art, bigger art, and needed different kind of space. So the metaphor failed. I couldn't just do a bigger Shaker house.

What was the solution?

FF: When you travel from the West Coast to Maine in one day, you get there late at night. I remember getting there in the winter, late one night, and the lights were on in the studio and I thought, “That's it. I'm home.” The glow–there's the light, there's somebody in there that's thinking about and making art. And so I talked about light, and the building as a lantern that is exuding the creativity that's going on in there.

And it so happens that a glass building is reflective, and you're not just looking at a glass box– you're looking at the sky and you're looking at the trees and you're looking at your own buildings because it's reflecting all of those things, and it's changing every season. And oh, by the way, you can put your Sol LeWitt mural behind the glass in the facade and that can be your signature. “Welcome to the museum. We've got a great piece of art.”

So again, it was in retrospect just like a building designing itself. I just put together the metaphors and the meaning.

Do you have UCLA projects of yours that you hold on to or even reference?

FF: I'm actually going through my archive now, and I just came across something and thought: What the hell is this picture? I unrolled it and it was my thesis project. It was supposed to be a solar-powered crematorium. And it was rejected. I presented it and I got very mixed reviews. There were a couple of people that thought, “This is amazing.” And there were others who thought: “What is this? What are you trying to do?” It offended some people. And so I put that aside.

It was not meant to be provocative. This was a project I designed shortly after my father passed, and it was in memory of him. I was thinking about him and mortality: Why not complete the cycle of life from taking the energy of the sun to being consumed by the sun, from dust to dust, ashes to ashes? And I took it really seriously. I thought it should really happen.

That’s a very different project than a museum, and yet, they both surround an experience. Is that how you conceptualize a museum–a space to encase an experience?

FF: The short answer is yes. It started by going to museums, but then it really started when I began working with artists and art galleries. I went from Caplin House, a real tour de force with so many ideas, to working with this porcelain artist, Elsa Rady, whose work was so pure and so precious. She was not at all interested in stories or metaphors or expressions. The art sitting on the shelf was the whole point of the space, and the space had to achieve that and value that. It's about proportions, it's about materiality. That experience was the whole start on my path in designing art spaces.

What about naming a project? Where does that enter the hierarchy of ideas?

FF: I often come up with the name before there's a project, before there's even a design. With the Colby example: It's the Shaker house, and everything flows from that. I tend toward simplicity and less; one of my many, many adages is “One less thing.” So, what can we take away? And generally you take something away and it's better.

As an architect, you have to be an artist, an engineer, a diplomat – have to be able to square off a spreadsheet, and you also have to be able to square off a corner.

FF: Another one of my ways of looking at things–which, people in my office, they roll their eyes, “There he goes again”–is the decision cone. On one end of the cone, it's really big and there's infinite possibilities, really philosophical. And then that goes down to a single point–because the building can only be one thing. So one way of looking at the design process is moving along a line from infinite possibility to one thing, and you have to keep condensing and contracting that infinite possibility over time, or you will never get a building. It's very philosophical and can be very artistic. But then, as an architect–it has to work.

I love this profession. I think it's an amazing profession for all of those reasons. I get to do amazing things that I sometimes can't believe people trust us to–put these permanent pieces in the environment that cost a lot of money, that will affect people's lives for generations. I take that really seriously.

I don't think I really fully understood what an architectural idea was until I worked with Frank for a couple of years. I would say that’s the most important thing that I learned at Frank's office–how an idea becomes a building. Not all architecture is idea-driven or needs to be or should be, but there is such a thing as an architectural idea, and that's what I strive for. It took four years of undergraduate school and three years of graduate school and two years of working in Frank’s office to really feel that I had a grasp on it, at least for myself.

I think that as the pieces began to fall together, I realized that I went to the right schools and got the right degrees and learned the right things. By whatever reason, I ended up at the right school, at the right moment in LA's history, literally in the right neighborhood. And I was just–I can't believe my luck.

Frederick Fisher, FAAR, AIA, is Founding Partner of Frederick Fisher & Partners. He received his Bachelor of Arts degree from Oberlin College in art and art history and a Master of Architecture degree from UCLA. He was Chairman of the Environmental Design Department at Otis College of Art & Design, and currently serves on the Board of Governors. Fred is also a board member of the USC School of Architecture, the UCLA School of the Arts, the Ojai Music Festival, and Lawrence University. As founder of FFP, he directs a practice that prides itself on architecture that is responsive, realistic, responsible, and revelatory. “If you create architecture that improves the lives of those who use it and its community, and brings pleasure and fulfillment,” he says, “then you’ve done your job as an architect.” Fisher is co-author of “Robert Venturi’s Rome” and is a frequent guest speaker.

Fisher’s long-spanning accomplishments as a design leader were recognized in 2013 with the AIA|LA Gold Medal. He received the Rome Prize in Architecture from the American Academy, and the Brendan Gill Award from the Municipal Art Society of New York for MoMA/PS1. FF&P received the AIA|LA Presidential Honoree 2020 Building Team of the Year Award and the Southern California Development Forum 2020 Design Award in Technological Innovation for the Santa Monica City Hall East, the AIA 20 Year Award for Bergamot Station Art Center, and the California AIA 2024 Firm Award.

- Exterior of Fisher's Caplin House

- Interior of Fisher's Caplin House

- Exterior of Eric and Wendy Schmidt Hall, Princeton University

- Interior of Eric and Wendy Schmidt Hall, Princeton University

- Axo of Eric and Wendy Schmidt Hall, Princeton University

- FF&P's 72andSunny, New York

- Common area of FF&P's Natural History Museum of LA County