Behind the Podium: A few questions with guest speaker Barbara Bestor

Sep 27, 2022

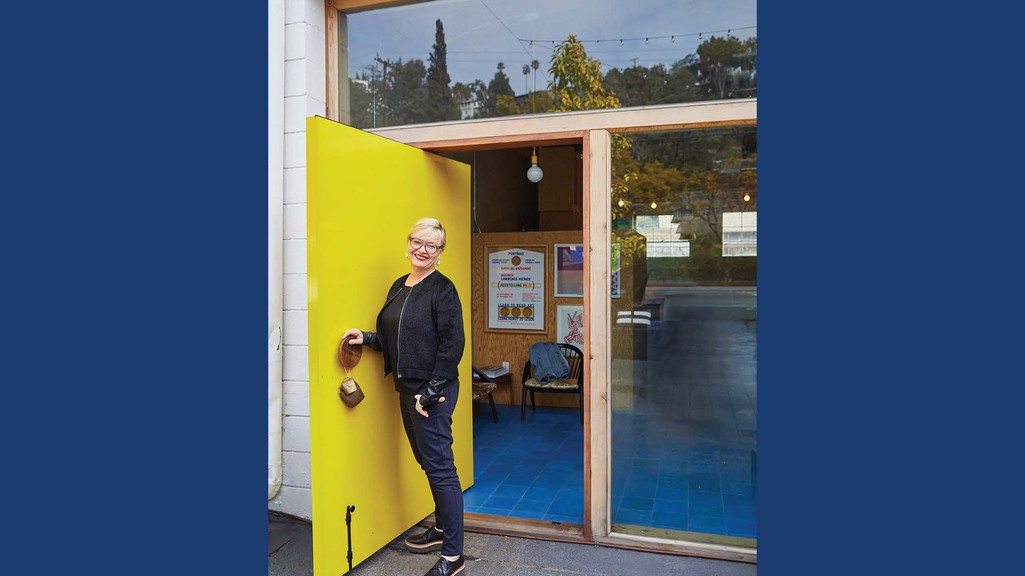

Barbara Bestor and her LA-based Bestor Architecture have designed a number of award-winning projects, including high-tech headquarters; a variety of form-driven residences, museum exhibitions, and retail projects; and an upcoming exhibition at LACMA. Bestor’s varied, creative, and aesthetically progressive body of work expands the territory of architecture into atmospheric urbanism.

Bestor presents a public lecture at AUD's Perloff Hall on Monday, October 3. In advance of her talk, Bestor had a conversation with AUD about her journey and what's on her mind today.

You grew up and studied in New England, then moved to the West Coast, specifically LA, for graduate school. What drew you out west back then–and what inspired you to build here?

BB: I was drawn to LA for its history of experimental architecture at smaller scales, everything from Irving Gill to Morphosis. I did an internship at Morphosis during college in 1986 and that solidified my sense that LA would be a great place to do architecture. After going to SCI-Arc and then teaching at UCLA, SCI-Arc, and Woodbury, my sense of the possibilities for Southern California’s architecture have expanded beyond the small-scale experiments to include embracing the recycling of our city itself with new ideas around housing and the streetscape as it impacts us today.

You established your practice not long after finishing your studies. What were the catalysts or currents around that move?

BB: I was lucky enough to start working on my own after grad school and went that way partly because I had done a brief stint at a large architecture firm and it was not for me. For the first ten years I found that the combination of teaching and a practice with small-scale commercial and residential projects gave me a great combo of conceptual thinking and engagement while simultaneously learning the tradecraft of building and client collaboration.

You’ve designed a lot of residential projects, and with Blackbirds, you nod to a crux many are considering: how to create high-quality housing within limited resources–whether land, finances, or otherwise–and to do so with density and sustainability in mind. With Blackbirds, you went for “stealth density.” What does this mean, and what are the unit-level or neighborhood-level benefits?

BB: Blackbirds is a project with 18 individual houses within a few lots that had previously held five worn-down houses. It brings density to the hills of Echo Park that historically consisted of Craftsman and Mission Revival homes from the early 1900s. The new houses at Blackbirds–and they are individual homes–share the size and scale of those previous residential typologies while carving out more collective space, including a landscaped, park-like, parking and multi-use area at the center of the land. The structures have larger apertures for views and sunlight, and the kitchens all turn to face the shared street. These elements created that sense of exchange and connection, encouraging connections on a personal level.

You’ve also designed across other typologies and genres, including high-tech headquarters, museum exhibitions, schools, commercial properties. What are some of the through-lines or themes that draw you into a project?

BB: I think a common thread between museum exhibitions and commercial spaces and even large-scale workspaces is the desire to create different experiential zones and multiple atmospheres within a larger envelope. To that end, we like to use super graphics, color, and occasional texture maps to bring sensorial atmospheres to spaces, without building separate zones or needing to use rare materials. I think a lot of that work falls under a category I would describe as interior urbanism: trying to make a diverse set of environments along public paths, with different elements appealing to different readers.

What materials or colors or textures, or typologies, are you experimenting with or thinking a lot about at the moment?

BB: Currently we are researching and exploring how collective housing can be implemented in Los Angeles. One idea for a new housing model proposes dense and diverse new city blocks to replace our underused industrial zones. Density can be an opportunity to design and build new communities and neighborhoods for the 21st-century city while also improving our infrastructure and our public, outdoor amenities.

For a couple of clients, we are currently programming and designing COVID-aware workspaces. We can support clients by developing flexible designs that adapt as environmental changes occur. The open office and the cubicle are no longer desired, the carbon footprint of commuting is unsustainable, and the interior urbanism of the office is radically changing.

For a design student or aspiring architect, what does the LA area uniquely offer as inspiration?

BB: Almost every month we learn more about the history of Los Angeles, a place where the marked layers of indigenous dwellers and our various waves of migration and building are very apparent in the urban environment. I was lucky enough to have [writer/urban theorist] Mike Davis as a teacher in grad school, and I feel like our city can handle a lot of critical thinking. We desperately need new ideas to envision abundance in housing and equitable access to nature. Personally, I see the groundbreaking architectural movements and experimentation that have happened here as direct inspiration for a new, different kind of practice in the 21st century, balancing the twin themes of continuity and breaking into new forms of architectural engagement.