Academics

Fall 2024 Courses

Each quarter, UCLA Architecture and Urban Design offers a range of courses and studios that situate, solidify, enrich, and inspire students' design skills and perspectives. Below, please browse AUD's offering of Fall 2024 courses and studios, with full descriptions and syllabi available for AUD students and faculty via BruinLearn.

Please note: This page is actively being updated and subject to change; please revisit for updates and additions. Last updated November 13, 2024.

Fall 2024 Courses and Studios, in brief

AUD Students and Faculty: Please visit BruinLearn for full syllabi and descriptions

This course provides a broad introduction to architectural ideas, framed through the lenses of history, science and technology studies, visual culture, media studies, and philosophy. Each week, students will attend two lectures that explore a shared theme, followed by TA-led discussions in sections. These themes engage with abstract concepts fundamental to architectural practice, such as “power,” “nature,” “measure,” “material,” and “labor.”

The lectures will emphasize historical thinking as a critical tool, helping us to contextualize architectural examples within their social and historical frameworks. We’ll investigate how a concept moves from abstract thought to a design principle, how it takes form in the world, and how it carries social significance across time and space.

Discussions in sections will focus on these themes, with teaching assistants guiding students through a detailed analysis of the assigned readings. These texts may deepen ideas introduced in lectures or challenge dominant perspectives by presenting alternative historical paths.

This studio is concerned with the boundaries and limits of architecture. By imagining two buildings nested one inside the other, the studio interrogates not only the threshold between the building and the world, but the many thresholds that reside within the architectural object itself. The current indeterminacy between living and working brought about both by crisis and our increasingly “seamless” and “interconnected” work-anywhere and live-everywhere model, has radically altered our understanding of these boundaries. Binary distinctions between living and working, inside and outside, private and public, individual and collective, have become difficult to pin down. Arguably, adjudicating spatial boundaries is architecture’s most fundamental role; how then has this blurring problematized our understanding of space?

The aims of this course are: 1) to introduce students to some long-standing debates in architectural discourse that open a territory for “theory” and 2) to relate those debates to issues in contemporary society. Lectures will focus on developments after the end of the 17th century, a period generally referred to as “modernity,” to explore how value was accorded to various forms of architectural production.

The didactic tool used to clarify the positions held by the historical figures presented in the course is an old one—opposition—where a dialectic is established between two seemingly irreconcilable positions. Sometimes that opposition is overcome (negated or sublimated), and sometimes it is radicalized.

Over the quarter, students will geometrize, transform, and multiply two alphabetic characters (student initials in Mies van der Rohe's typeface) to create two distinct shade structures: one post-and-beam and the other volumetric. With their definitive boundaries established early in the quarter, the two structures will develop simultaneously and dialogically.

The disciplinary architectural production is fundamentally situated between the imaginary and the eventual artifact. While the general assumption is that this artifact is a building, the reality of architectural output and its daily labor is more often dedicated to the generation of architectural mediations such as drawings, models, and images. Even though the realized architecture as building is the physical manifestation of the spatial imaginary, this reality alone is not the only verification of architectural sensibility and intellect. Our expanding disciplinary vault is full of projects which only live and thrive as drawings, models, and images, representing the architectural ideas held within them.

It is usually this material that challenges the norms and defines new frontiers of our discipline through speculative ideas regarding our built environment; it is usually through this material that we stake theoretical positions to construct new agendas; it is usually this material that allows us to contemplate competing discursive trajectories; it is usually through this material that we delve into new aesthetics; it is usually this material around which we engage one another for collective and diverse intellectual growth.

As architects, our everyday labor does not include the act of building. However, we sketch, draw, model, make models, render, animate, simulate, write, and talk to communicate our architectural positions. We engage fellow architects, academics, engineers, private and public clients, donors, community boards, the broader public, building departments, contractors, fabricators, and manufacturers for various purposes and with varying agendas. Our ideas, whether they are conceptual, technical, or descriptive, are mediated through a number of tools to communicate our intentions. Architecture is a multi-medium effort that requires expertise from a broad range of technologies and channels of mediation.

The conceptual rigor and the critical skill sets one needs to possess within the paradigm of ever-evolving technologies of mediation are paramount in one’s learning and growth in the discipline of architecture. This sequence of three required courses in the first year of the Master of Architecture program aims to focus solely on the development of conceptual depth, aesthetic sensibilities, and the fundamental skill sets to engage conventional and emerging technologies toward the mastery of architectural mediations.

This lecture course studies the quintessential characteristics of American urban and suburban form as they developed historically and have been systemized by the design and planning professions since the late 19th century. The course is organized thematically around the grid, park, neighborhood, cityscape, sprawl, downtown, housing, and environment, and asks how American republicanism and sentiments of anti-urbanism shaped American urbanism, as well as how disciplinary and professional boundaries between architecture, landscape planning, and urban planning were drawn, and in turn, gave rise to urban and environmental design. While drawing primarily from the histories of New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles, we will also situate their historical developments in transnational and global frameworks, extending beyond Europe to India, China, the Philippines, Iran, Nigeria, and Tanzania.

What is research for design? Does it follow a method? This seminar takes this elusive nature of research methods as a chance to attend to the habits and rituals that have long shaped design tradition, including what counts as criteria of evidence and value in architecture.

Across three broad themes—field, documentation, and project—we will begin by studying the institutional and disciplinary lineages of research methods in design. We will then examine how these methods structure the visual media, techniques, and styles we use to communicate our work and explore new possibilities. A series of workshops throughout the quarter will test out a variety of methods—interpreting texts, invoking references, observing sites, writing briefs, creating diagrams, images, models, and telling stories. The aim will be to curate an archive for your own design project at large, one that situates itself relative to the field and identifies relevant working methods.

Description coming soon

Description coming soon

In this seminar, students will be tasked with creating their own films in which architecture plays the lead role. Students will begin by choosing a house of architectural significance and digitally recreating it in meticulous detail. The ambition is for your architectural “actor” to breathe and project the same life it embodies in the physical world. Once your 3D recreations are complete, you will work in groups to devise narratives to project onto these structures.

Similar to Koolhaas Houselife, these narratives are meant to explore new perspectives that have not previously been known or seen, offering subtle evaluations of how architecture responds to domesticity and human interaction. Students will reference Antonioni extensively for guidance on framing, lighting, composition, and capturing the bond between architecture and cinema.

The final output will be a series of films that help uncover new understandings of known architecture through the power of cinema. Each student will produce a 1- to 2-minute animated film using either Unreal Engine or Cinema 4D with Redshift. The students’ animations will consist of 3D-modeled architecture, highly detailed props, animated characters, and dynamic sets. Through this exercise, students will also develop a deeper understanding of how to create cinema within the digital realm. This level of process and articulation will ultimately translate to their own projects in the future.

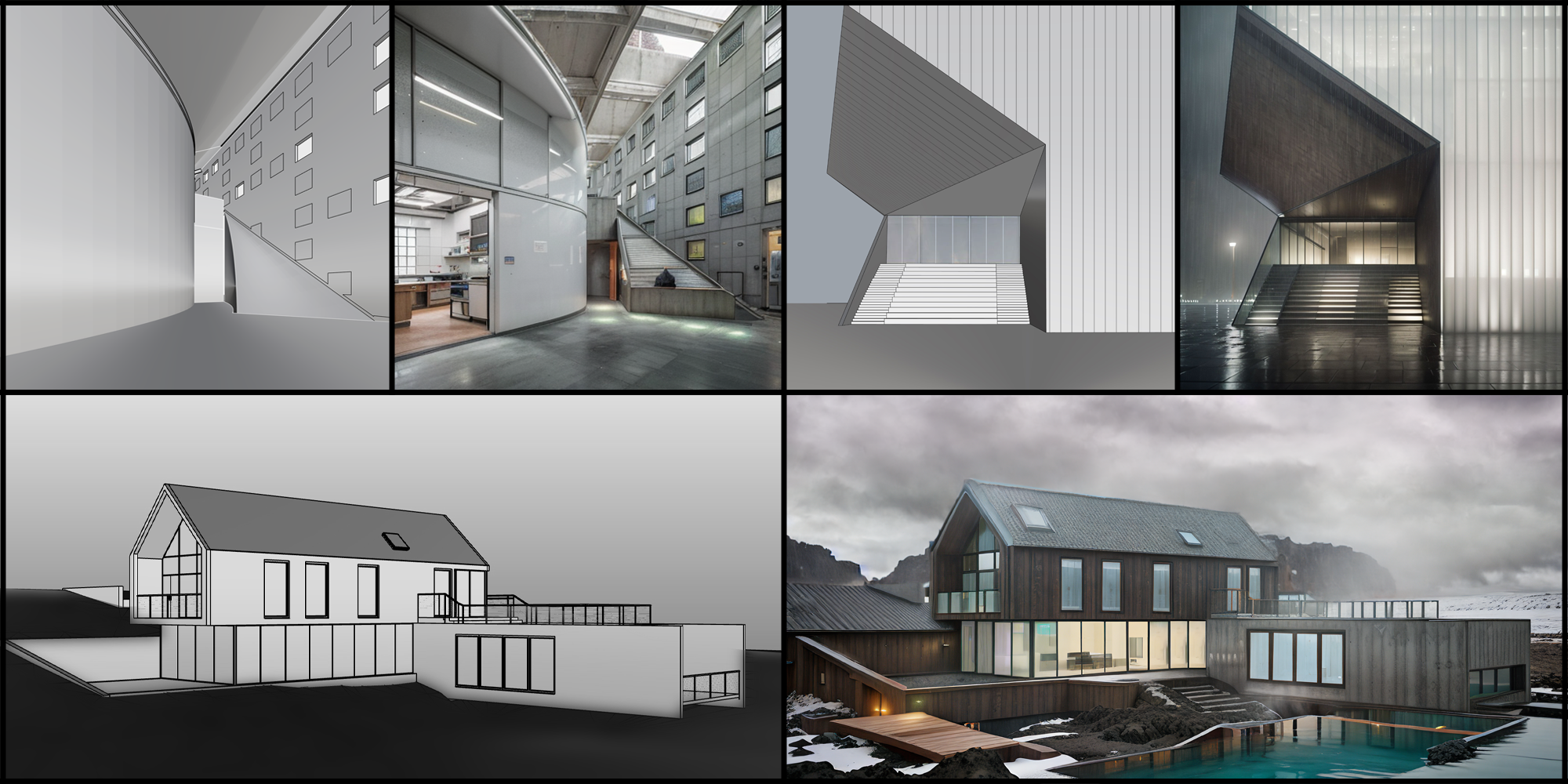

In this course we will be using generative AI to construct synthetic architectural representation. In the realm of artificial intelligence, the creation of an image is an intricate and complicated interweaving of algorithms and data, that, while devoid of a ‘real’ origin, can be strikingly ‘photorealistic’. This AI-generated image, a simulacrum, is a mirror held up to a reality that doesn’t exist, reflecting back an illusion of authenticity. It encapsulates a carefully curated identity — an identity that we hope to control as another tool in our arsenal for design and representation.

The quarter-long project will focus on leveraging various machine learning models to generate, alter, edit, and manipulate the representation of a simple screenshot taken from Rhino. Using a combination of software students will produce detailed rendered images and/or video of a simple Rhino massing. Students will research, test, and manipulate the inputs and versions of the models as well as use a variety of control techniques to produce the desired output. Each student will aim to control, edit, and understand, the workflow of editing and generating each layer of the produced image.

In this seminar, students will develop projects situated in the complex topography of the hills in Los Angeles, specifically in the hills just north of West Hollywood. This exclusive enclave of Los Angeles boasts some of the most expensive real estate in the country and showcases some of the largest homes. The stark contrast to the city below exemplifies the enforced segregation, largely through design, that exists in Los Angeles.

Transit and housing have a complex, intertwined relationship. The suburban homes of Los Angeles were only made possible due to the private vehicle, which enabled easier long-distance travel. This phenomenon led to "white flight," exacerbating segregation in cities. In many cities, including Los Angeles, segregation was embedded into law. Mass transit was devastated and ultimately eradicated in many areas, further deepening dependency on private vehicles.

As the housing crisis in Los Angeles grows increasingly dire, new strategies for densification are needed—ones that also address the abhorrent inequality and segregation growing in scope and intensity. How can architectural thinking provide new possibilities to solve some of these issues, while also offering opportunities currently not feasible? How might mass transit aid in developing denser housing typologies that connect inhabitants to the rest of the city easily?

This seminar is interested in how architectural speculation can potentially reshape the current zeitgeist. It will explore housing and transit speculation rooted in site-specific research and methods of representation. Within the scope of the seminar, we will develop implementation strategies that consider economies of labor and materials.

In architecture, the program is a powerful concept and tool. It sits squarely at the intersection of the discipline’s socio-cultural potential, the architect’s agency, and the building’s impact. To advance spatial justice as well as climate action, architects can begin with the program. Within architectural discourse, the concept of the program broadly ranges from building occupancy to project marketing, design process, and urban narrative. In practice, the program-as-tool is implicated in some of today’s most pressing concerns: gentrification, inequality, affordability, persistent segregation, gender identity, health, housing, and environmental issues, as well as questions about metrics, evidence-based outcomes, and building standards. This quarter, we will advance conventional thinking about urban- and building-scale programs, read theory that expands the program’s role in architecture, and gain insight into programming’s politics.

We will undertake a comprehensive look at the program, as well as an in-depth examination of the program as a means to advance health and well-being. Historically, urbanism and architecture’s roles in our well-being have been highlighted during epidemics: consider John Snow’s maps tracking the mid-19th century cholera outbreak in London, W.E.B. Du Bois’ visualizations of Black health inequities and segregation in Philadelphia in the 1890s, or Colomina’s rereading of 20th-century modernism and X-ray imagery through the lens of tuberculosis. More recently, space and well-being have been linked in myriad contexts: global warming and urban heat island effects, homelessness and lower life expectancy, obesity and the suburbs, inequitable access to parks, and the spatial complications of the Covid-19 pandemic, to name a few. These examples highlight the multifaceted implications of architectural programming in relation to health: Whose health is affected? What evidence is available? What is design’s impact?

The course will counter the received wisdom about the program as a packaged statement about function that a client gives to the architect or as a list of square footages that the architect provides in return. Instead, we will investigate the program’s conceptual production and, importantly, its creative, formal potential. Our assumption is that the program begins as a narrative composed of text and image if it is to shape the built environment and that it is deeply rooted in and consequential for everyday life. To engage these issues, we will explore theory about the program (through readings, lectures, and discussions), which is most provocative when taken in the context of practice (through architectural case studies and the quarter-long programming-and-design term project).

This studio is primarily concerned with three things. The first is more important than the second, though the second greatly affects the first. The third is just always there.

The origins, lineage, and provenance of ideas (in all the arts, but here, as identified through the medium of architecture).

The use of image-making Generative AI tools in 2024.

Buildings as spatial and material artifacts and how we document them.

This studio’s primary medium will be timber, distributed as sticks, stacks, and composites, representing its various engineered forms. The studio is invested in understanding how engineered timber might once again alter what we build while simultaneously reducing environmental impact. From mass-produced dimensional lumber to plywood to CLT, the manufacture of timber’s material form reshapes architecture’s spatial and structural orders and its aesthetic effects. We will briefly study and catalogue a selection of timber’s architectural contributions, learning from references and developing technical vocabulary along the way to understanding timber’s future disciplinary potential. The studio argues that material distribution is deeply conceptual. Within this conceptual framework, force flows, space emerges, and aesthetics bloom.

Students will develop timber tectonic systems in the creation of a spatially intensive building organization poised between figure and field. The project will be a public market with a train passing through it, near the current Del Mar Station. The site is located between Pasadena’s Central Park to the west, Green Street to the north, the historic Route 66 to the east, and Del Mar Avenue to the south. The site implicates both the infrastructural and architectural, linking Southern California’s transportation history to the material history of the Arts and Crafts movement and the urban spatial typology of the paseo. A program document will be distributed in class.

Why timber now? Timber is a highly workable, renewable resource. Timber assemblies are dimensionally precise, especially when manufactured offsite. CNC-controlled manufacturing economically activates part shape, length, thickness, and edge geometry. These assemblies interface easily with other materials, yielding hybrid material and tectonic assemblies. Timber’s production requires less energy than other building materials and results in fewer carbon emissions than either steel or concrete, resulting in both embodied carbon savings and carbon sequestration. Timber is also familiar and popular. Appreciated by a wide range of audiences, its invigorated use might open the door to architectural experimentation precisely when, culturally, this door appears to be closed. Experimentation offers possibilities, allowing us to ask questions, apply both intuition and expertise to new challenges, and importantly, produce novelty in light of—or in spite of—new constraints. To begin, we will investigate a catalogue of timber building precedents to frame and draw out related disciplinary potentials.

In this studio, we will explore timber’s potential as material and atmosphere by organizing assemblies of sticks, stacks, and composites. “Sticks” refers to linear elements, often distributed at even intervals. Dimensional lumber is the most common stick; sticks become heavy timber when the cross-section expands, becoming posts or beams—the components of spatial matrices. “Stacks” refers to elements that make up piles or interdependent components that transfer force from one element to the next through direct bearing. “Composites” fuse elements to perform collectively. Wood composites rely on joinery, glue, straps, screws, and the like, typically as arrays of laminated members, from glulam elements to cross-laminated timber. Each of these categories of material distribution has a direct impact on spatial atmosphere, spatial boundary, and building form.

"Where the material goes, the force flows." This rhyming catchphrase was etched in my memory in a university lecture hall years ago. Yet its lessons are far more significant than one might think. This concise phrase links material, geometry, and force in relationships that are operative. Without this triad, not only would we lack shelter, but we would also lack a broad and captivating history of architecture. It is precisely material coursing with force that has configured centuries of social interaction, political debate, religious liturgy, and a central disciplinary vector of architecture. This studio takes the material history of timber in architecture for what it is: an incredible demonstration of the ingenuity and expertise that has contributed to architectural knowledge. We will aim to expand on these lessons, choreographing material, geometry, and assembly not only for structural and environmental performance but also for atmosphere and aesthetics.

There is an intriguing school deep in the Himalayan Mountains. The school is called Jhamtse Gatsal. The name means the place of love and compassion. It’s a home and school for children. The orphanage is also a school for them. This school is in one of the most remote areas in India yet known to have extremely high-quality education. The school is 500 km away from the city deep in a mountain. While the school allows them to choose diverse profession, 95 percent of the children go to university. That is unusual in India, where only 20 percent goes to university. They achieved the unique quality with unusual method. The education is based on sharing. As their orphanage is made to share every aspect of their life, they share knowledge each other. The knowledge turns into wisdom. While knowledge belongs to each person, wisdom is the attitude and method to bind people together. In the school knowledge is not the measurement to compete each other. Knowledge is nothing more than a piece to share with others. I found the most advanced education in the most remote place of the planet.

I want you to design a school to share knowledge. The school is not a place to train children. There is no competition. There is a big difference between teaching and learning. The teaching is to give knowledge to children, but learning is the process for children to take spontaneously. The class is not going to be divided into age groups. Architecture is not a thing but a situation. The school needs to be the place to provide opportunities. There will be children having different learning speed. The children know when they are ready to learn. The school is not only about STEAM. That needs to be the place to share and help each other. The rule of the school is only love and compassion There will be about 100 children from age 3 to 18. Please find a way to put them together.

In the context of a rapidly evolving global landscape, the adaptive reuse of buildings has emerged as a viable strategy for addressing the complexities and challenges associated with urban development. Adaptive reuse is now considered a pivotal component in strategic urban interventions, tackling critical issues and cultural and economic challenges related to managing the expanding and diverse inventory of underutilized buildings. This strategy reimagines and repurposes existing structures, often integrating historical and contemporary architectural elements to extend their lifecycle. By doing so, adaptive reuse mitigates the environmental impact of demolition and new construction while fostering sustainable urban regeneration. It also acknowledges the cultural significance of local traditions and heritage.

In their essay, Adaptive Reuse: A Critical Review, F. Lanz and J. Pendlebury argue that the growing heterogeneity of ordinary buildings amplifies the complexity of adaptive reuse strategies, which must be highly flexible, context-sensitive, and responsive to the specific architectural, social, and economic fabric of each site. This process not only conserves energy and materials but also contributes to shaping more resilient and culturally vibrant urban environments. This perspective enriches the conceptual framework of adaptive reuse, positioning it as a critical lens through which to analyze and interpret the transformation of the built environment as a dynamic process of re-appropriation and re-signification.

Such an approach entails not only the physical reuse and revaluation of spaces that have lapsed into inactivity but also involves a deeper reconceptualization of the spatial, temporal, and socio-cultural layers embedded within these buildings. This reactivates their associations, memories, and behavioral patterns, infusing them with renewed relevance.

British artist Alex Chinneck’s From the Knees of My Nose to the Belly of My Toes (2013) and Telling the Truth Through False Teeth, along with Richard Wilson’s Turning the Place Over, are examples from the art world that broaden the current significance of adaptive reuse strategies. By discovering the unique and extraordinary potential in everyday objects and architecture, Chinneck "weaves fantasy into existing materials, objects, and structures."

He argues that his work is “always contextually responsive, conceived with the visual language, material palette, heritage, and future objectives of the location in mind. This philosophy lends the work a sense of belonging to the place in which it stands, heightening the believability and regional personalization of the sculpture.”

One example is his unzipped façade of an old building at the Torotona Design District in Milan during Salone del Mobile 2019, where, through the use of the zipper, he has “opened up the fabric of a seemingly historic Milanese building to playfully reimagine what lies behind its façade, floors, and walls.”

In this studio, you are not just architects—you are worldbuilders. The room is your canvas, the space

where your story takes root. Let the world unfold through the room, layer by layer, frame by frame.

As we navigate this year, the room will act as your gateway—a carefully crafted space that reflects the world around it. Whether through subtle, mundane changes or dramatic shifts, the room will evolve. Your challenge is not just to design the room, but to craft a world through that space, to think about what the room says about the people, technologies, and cultures that shaped it. The room will act as a mirror, showing us both the world inside its walls and the world outside, shifting across time. The success of your worldbuild lies in its ability to support the narrative while simultaneously revealing the depth of the world beyond.

Worldbuilding is the subtle, intricate act of designing the environment in which a story lives. It is a craft that defines the space where narratives unfold, the backdrop against which characters breathe, struggle, and exist. A successful worldbuild creates coherence—a bond between the space and the story—so that the environment feels lived-in, integral, and essential to the narrative it holds.

When the world doesn’t fit the story, the fabric unravels, and the immersive power dissolves. Every single element within that world becomes a cue, a guide to the audience's understanding of the narrative: the atmosphere, the objects, the colors, the quality of light, the passage of time, the sounds, the texture of materials, and even the way a breeze drifts in from a window.

This year, we are turning our attention to a single room as the locus for an entire universe of stories. A room, on the surface, seems limited—a static space with four walls. But within those boundaries lies the potential for an infinite array of narratives. The room is not just a container; it’s a reflection of the world beyond it. It is the way we come to understand time, space, and the lives lived within it. The objects that populate the room, the marks left behind, the shadows cast at different times of day, all create a dialogue with the outside world. Through this room, we will see the world, and through its design, we will define the narratives that take place within it.

Worldbuilding is more than set dressing. It’s about creating a cohesive language between the space and the story it tells. The architecture of the room, the way the light falls across the floor, the view through the window—these are not just background elements; they are as crucial to the narrative as the characters who move through the space. The room will speak to the world it inhabits, telling us about the society that built it, the technologies that shaped it, the people who lived and worked within it, and the cultures that evolved through it. A well-designed room allows the audience to feel the presence of time, the layering of experiences, and the evolution of the world outside its walls.

Technology Studio scrutinizes the heavily mediated interplay between form, image, and language within the media-saturated human experience. With an acute focus on innovation and provocation, students explore the fusion of architectural design with media art and technology, challenging the way we perceive, experience, and interact with buildings, cities, and online social platforms.

The 2024-25 topic Temporal/Spectral builds upon the ongoing research of the Studio to imagine environments that are created through a cyberphysical fusion between materials and media, focusing on the meaning and impact of envisioning architecture as a construction of ideas through vision, sensation, and presence.

The studio course will explore contemporary issues in urban design and architecture, specifically the development of proposals responding to climate change. The aim will be to inspire public interest in our physical environment through inventive design and regenerative strategies.

Since many kinds of interventions will be needed to slow climate change, one contemporary role of architecture is to excite designers, engineers, and inventors to think up and realize all kinds of imaginative measures to contribute to the most important challenge of our lifetime. The climate crisis won’t be solved by one idea or technology: the more approaches there are, the better. Architecture can instill a collective spirit of experimentation to accomplish this end.

The project site is Sea Ranch, the legendary 7,000 acre community in Northern California begun in the

1960s. Master planned by landscape architect Lawrence Halprin, the coastal community is best known for its design ethos to harmoniously integrate architecture with nature. Buildings are nested in the natural landscape, situated to highlight the overall beauty of the Sonoma County ecology over individual buildings.

Along its 10-mile long stretch, buildings are set back from the oceanside cliffs to further accentuate the landscape features of the master plan. Trees and marine grasslands dominate the terrain with common buildings and homes built close to tree rows so as to maintain as much open land as possible. As a result of climate change, Sea Ranch must now rethink its iconic landscape. The defining logic of the master plan puts it in peril of destruction. Experiencing increasingly high temperatures, this forested coastal environment is now vulnerable to wildfires. The original guidelines to situate buildings close to nature increase the risk of fire, since the closer buildings are to vegetation, the greater the likelihood of ignition.

The studio will ask, How does a community integrate architecture and landscape while mitigating

wildfires? How does a place best known for knitting together buildings do so when that is a fire risk?

Vegetation + Buildings = Ignition. This preventative logic of distancing buildings from nature is reinforced by California’s fire hardening requirements. Like the rest of the Golden State, Sea Ranch’s buildings must not have landscape immediately around them.

The studio will propose a new master plan for Sea Ranch that adapts the environment to our climate

reality by lowering the chances of wildfire. More importantly, we will attempt to allow Sea Ranch to thrive - to bridge together humans and nature in its next evolution, as the region experiences extreme weather during future decades this century.

Ceremony, which exists in various forms worldwide, is an interesting architectural phenomenon in which space and human action are intimately connected and extend beyond materiality into spirituality. While many ceremonies are strongly linked to religion, the tea ceremony, one of the most essential rituals in Japanese culture, is unique in that it is non-religious yet strongly connected to spirituality and has spread globally through the activities of Urasenke.

However, the current tea house and its associated rituals are still strongly dominated by the traditional Japanese form of sitting. They still need to be fully integrated into the many multicultural standing forms. In this studio, we will study the tea ceremony in a non-Japanese cultural context, and through the process of designing and studying its transformation, we will attempt to treat space, tectonics, tools, human action, and spirituality as one continuous design.

Fall Quarter (October-December): Research about Tea Experience

In the fall quarter, students will learn about the history of Japanese architecture, teahouse architecture, and the tea ceremony through seminars by various experts. Also, they initiate case studies of teahouses and the tea ceremony rituals performed in them, as well as other ceremonies held around the world and their relationship to the place of the ceremony, and discuss each's uniqueness and commonality.

Trip To Kyoto (December, after Fall final)

The students will visit teahouse architecture and experience tea ceremony in Kyoto with the cooperation of the Urasenke as well as the visit to traditional architecture and gardens.

Dec16 (Mon) Ura sennke tour( yuu-in, Konnichi-ann)

Dec17 (Tue) Katura Rikyu, Tai-ann,

Dec18 (Wed) Kennninnji(Zazen), Daitokuji (Kohou ann),

Dec19 (Thu) Free

Dec20 (Fri) Final review @ ?

Winter Quarter (January-March): Design of the Tea Ceremony

In the winter quarter, the meaning of wellness in contemporary society, its relationship to ritual, and its role in achieving it will be studied. Based on the knowledge gained in the previous quarter, the students will also design scenarios of how the tea ceremony could be interpreted, translated, and performed in contemporary non-Japanese cultures, in what form, at what place, and with what utensils and food, and design a space in which the ritual could take place. Also, they will create a design brief of the place of the ceremony based on the scenario.

Spring Quarter (March-June): Design of the Tea house

The students will design a contemporary teahouse based on the scenarios and design briefs designed in the previous quarter. The exhibition and the symposium will be held as a culmination of the initiative.

In collaboration with Reijiro Izumi (Urasenke), Tohru Horiguchi (Kindai University, Japan), Michelle Liu Carrigar (TFT, UCLA), Yusuke Tsugawa (David Geffen School of Medicine, UCLA), and Ken Tadashi Oshima (Architectural historian, University of Washington)

Year-long studio

This research studio involves the engineered ecology and resultant aesthetic implications of the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power’s Dust Mitigation Project at Owens Lake, a large site in eastern California of major environmental, historical, political, and infrastructural significance. Until very recently the largest single source of dust pollution in the U.S., the studio examines control methods developed by LADWP to manage this difficult landscape: a complex synthesis of fields, pools, plants, animals, microorganisms, chemicals, minerals, roads, berms, dams, plumbing, power lines, grading, gravel, roads, sensors, and salt that is only partially visible to the human eye. The effects of these re-workings of the landscape are striking, inevitably aesthetic in their expression. Our work imagines a near-future evolution of this infrastructure toward strange new landscapes, turning radically empirical environmental engineering techniques toward a more expansive, aesthetic dimension. The design problem imagines arguments, in the form of visual albums and design projections for the creation of a new national monument for this gigantic Anthropogenic landscape.

Year-long studio

A mission or vision statement is not a vague platitude. These are articulations of unique competence and measurable goals.

For three years in the MSAUD program, Professor Greg Lynn taught a two-quarter seminar that used corporate brand defining tools as a critical instrument for historical and cultural research. For the last two years, Lynn's MArch Research Studio used those tools as design method. The experience with goal setting and defining personal criteria for success can assist in team building and studio culture alignment in future professional practice.

The Fall 2024 and Winter 2025 quarters of Professor Lynn's 2024-2025 year-long Research Studio will focus on the formation of critical architectural concepts with clear measurable consequences. The disciplined skills of problem formation, value decisions, radical editing, profundity, and extreme clarity of communication will be applied to the studio. You will define your own design brief during these two quarters. During the Spring 2025 quarter of the research studio, everyone will share a site where a building design will be executed with relevant comprehension guided by personal Mission and Vision statements.

To define individual criteria for success, the studio requires a calibration of ambitions with design skills and conceptual competence. This culminating studio pedagogy has been crafted specifically for the third year graduate Research Studio at UCLA. The focus on studio culture requires: listening and trust in peers’ feedback; self-awareness of personal strengths and limitations; and clarity of communication that is actionable and intelligible by others without ambiguity. This studio will disappoint if you are seeking one last new method or experiment before you graduate. The studio is a good place to articulate exactly what it is that you do well before you graduate.

Year-long studio, with precedent in 2022-2023's and 2023-2024's "Fit for the Future" studio

Wearables protect us from the climatic conditions, they provide privacy, comfort and they also reflect our style and personality. Building facades in the same way, provide protection from the weather, comfort, privacy and showcase typology and style. The link between architecture and fashion is a perceptible phenomenon in both theory and practice through many contemporary pioneers including Frank Lloyd Wright, Adolf Loos, Coco Chanel, and Joseph Hoffmann. Designing the architectural surface was frequently understood as being similar to designing a garment. The foundation of this connection between textiles or dresses and architecture had been laid in the mid-19th century by architect Gottfried Semper’s “Principle of Dressing.”

This year-long research studio, in its third cycle, will investigate the relationship of fashion and building skins, and research how buildings of the future can have skins that are performative and are 3D-printed with innovative sustainable materials. Across the world, temperature extremities are rising into previously unimagined realms and summers are developing to record setting heat. Extreme heat affects health and wellbeing and it affects how we occupy and use buildings. Climate change is experienced across the world in changing weather conditions such as more frequent fires, droughts, storms and flash floods. Ground-up construction will diminish in urban environments and increasingly be replaced with retrofits. Within the studio we will rethink how to design retrofits of existing buildings, providing them a new wearable skin, and one that responds to extreme climatic conditions.

Surge in use of 3D printers in the construction industry for making precise final products, developing prototypes while lowering the production and materials cost and increase in adoption of green buildings and structure drive the growth of the global 3D printing construction market. The market across North America held the largest share in 2021, accounting for nearly two-fifths of the market. The path towards a sustainable future requires a transition from the current linear, extractive, toxic construction practices, towards circular, bio-based, renewable materials and methods. This shift has the potential to dramatically reduce the natural resource needs and carbon footprint of growing cities and infrastructure, and is critical to deliver on the Glasgow Climate Pact.

In this course, students will explore the evolution of image-making technologies and their profound effects on society, culture, and politics. From ancient cave paintings to AI-generated images, the class will analyze how these technologies not only change the way we create and view images but also shape the world around us. Students will investigate the ways in which image-making tools influence movements—whether at personal, national, or global scales.

Throughout the course, students will contribute to a collaborative timeline and produce individual research booklets that catalog key image-making technologies and their impacts, creating a comprehensive atlas of how these innovations have affected our understanding of the world. The course encourages critical engagement with the ideological and cultural power behind the creation of images and how these tools have transported ideas across time.

Description coming soon

The seminar will provide students with the opportunity to develop a disciplinary position and strategy. Selecting from one of the practices below, each person will formulate a position statement to differentiate the practice from all others in the field. Based on the statement, each student will create a strategy for the practice to thrive. For the purposes of the course, ‘strategy’ will be defined as: the creative alignment of available resources to achieve an intended outcome.

This is the first studio in a core sequence within the MArch I program at UCLA. The core curriculum intends to expose students to how architecture is conceptualized, developed, and represented through a series of rigorous design methodologies rooted in continuous cultivation and evolution of architectural fundamentals. The core studios consecutively expand in scope and complexity, building towards more personalized explorations and experiments conducted in the last year of the program in the advanced and research studios.

As the first in the sequence, this studio explores issues that are central to the discipline – space, form, and representation – encouraging students to develop their own position and understanding of the fundamental methods, tools, concepts, and design strategies, which will ultimately project beyond the first quarter.

The studio posits that architecture can transcend any specific program and its duration, and can establish spatial and tectonic order that can lead to the invention of new programs during the life of a building. Unlike subsequent studios, during which an analysis of a given site or program may drive the design process, this studio reverses the sequence and instead begins with the organizational and experiential capacity of form. As such, form will inform the program and context within which it is situated. Rooted in representational conventions, namely the orthographic projection, students will experiment with the creation of proto-architectural conditions, examining how their formal and representational approaches imply specific ways of inhabiting and experiencing space.

^1 Proto-architecture in this context refers to representational artifacts that have many of the aspects associated with buildings but are not yet fully finished architecture.

Los Angeles grapples continually with the environmental challenges intrinsic to its geographical location. These challenges encompass geological instability, a highly diverse topography, recurrent wildfires, extreme temperatures, and a persistent scarcity of water resources. The city confronts an unrelenting demand to sustain its ever-expanding metropolitan existence, particularly as the compounding effects of climate change exacerbate its immediate environmental milieu.

Accommodating the diverse communal habits of urban living necessitates extensive infrastructural undertakings and innovative solutions. In an epoch characterized by a shift toward more subtle and concealed infrastructures, Los Angeles continues to rely on extensive physical infrastructures to secure its natural resources, a prerequisite vital for its survival as a metropolis.

Amidst the backdrop of adverse climate change, characterized by arid conditions, reduced precipitation, and frequent droughts, the foremost concern in Los Angeles pertains to the procurement of natural water sources for the city. Historically, the supplying of water to this arid locale has been a monumental endeavor. An intricate network of infrastructure facilitates the delivery of water into the city, primarily sourced from the Sierra Nevada Mountain Range via surface aqueducts and tunnels. Within the metropolitan boundaries, this water undergoes management via an expansive framework of dams, reservoirs, channels, and pumping stations, culminating in its delivery to individual faucets.

The development of essential civic infrastructures has traditionally served as a marker of a civilization's advancement, aiding in the organization and facilitation of evolving communal needs and desires. Present-day urban centers rely on public/private institutions to oversee and maintain these infrastructures, serving as intermediaries between resource cultivation, distribution, and public consumption. In a field invested in the cultural impact of architectural interventions, the conspicuous absence of influence and participation in envisioning the integration of civic infrastructures, which fundamentally impact the equitable and just distribution of resources to the public, warrants profound consideration. It is against this contextual backdrop that the studio puts forth the prompt to examine the agency of architecture in engaging with and speculating on its relationship to larger systems.

The ongoing transformation of open-air water reservoirs in Los Angeles is driven by contamination issues that have compromised the quality of the city's drinking water supply. This transformation results from two new regulations enacted by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, aimed at mitigating microbiological contamination and averting risks associated with microbial pathogens and disinfectant byproducts (as stipulated in the EPA Stage 2 Disinfectants and Disinfection By-Products Rule and the federal Long-Term 2 Surface Water Treatment Rule (LT2)). Contaminants encompass a spectrum of sources, including animal waste, runoff drainage, algae, and human influence. Notably, Silver Lake and Ivanhoe Reservoirs have been decommissioned, paving the way for their conversion into new recreational spaces for the public. Several other reservoirs, such as Upper Stone Canyon, Santa Ynez, Eagle Rock, Lower Franklin, Elysian, and Green Verdugo Reservoirs, have been equipped with floating covers to prevent contamination. While covering existing reservoirs represents a cost-effective solution, it falls short in fostering a high-quality environment conducive to thriving public recreational spaces. Moreover, it does not address the need for increased capacity through the construction of new reservoirs.

To offset the loss of volume resulting from the decommissioning of Silver Lake and Ivanhoe Reservoirs, the Los Angeles Department of Water & Power (LADWP) initiated the construction of two new reservoirs situated to the north of Griffith Park, denominated as Headworks East and Headworks West. These reservoirs are conceived as substantial subterranean concrete structures concealed beneath the grounds of a forthcoming recreational park area, representing a convergence of concealed infrastructure and artificial landscapes into a public park setting. Headworks East has already reached completion, while Headworks West approaches its final stages. Within this context, we find an opportune juncture to intercede, exploring alternative potentialities that transcend the conventional paradigms of infrastructure design.

In light of the multifaceted challenges posed by the environment and the imperatives of sustainability, architecture's agency in reimagining the deployment of natural resource infrastructures in Los Angeles emerges as a pivotal discourse. The convergence of environmental constraints, regulatory directives, and the inherent potential for architectural innovation necessitates a concerted examination of architecture's role in the recalibration of infrastructural paradigms to ensure equitable access to vital resources within the urban context. The transformation of water reservoirs, as exemplified by the Headworks initiative, offers a compelling vantage point to scrutinize the evolving role of architecture in forging resilient, resource-efficient, and public-centric imaginaries that meaningfully engage the urban fabric.

Structures I, AUD 431, is the first part of a year-long, three-part exploration into structural thinking. Structure is certainly used to support architecture, but, is also space defining, form generating, and aesthetically engaging as well. The Golden Gate Bridge has majestic structural towers and fluid structural cables. They support the roadway. But they then define the architecture, the roadway being almost structurally incidental. The dome of the Pantheon encloses a wonderful, large circular space. But the architecture is certainly in the presence of the dome itself.

Structures 2 continues the understanding of span from Structures 1. How span works is central to what is built. Both opportunities and limitations are found here. Columns and walls play a similar role, but to a lesser degree. We look first at columns this quarter and then we look at wood as a building material, as a spanning material, a material that is undergoing profound changes as we move away from solid-sawn members and more to engineered members. Mass Timber is expanding these changes. Many of the ideas discussed are similar to those of steel, many are different. The course will also look at an introduction to lateral load design, a topic more fully addressed in Structures 3.

Students will gain an understanding of important features of architectural practice, including the architect’s roles and responsibilities, contractual and professional relationships, and instruments of service. Today’s range of project delivery systems will be introduced, including emerging technologies and fabrication methods. Presentations and discussions will review graphic and textual conventions and standards, regulatory requirements and processes, and steps necessary to bring an architectural project to fruition. Students will learn about the path to licensure, and tools to help them manage a practice, coordinate consultant input, and mitigate exposure to risk.

Description coming soon